“Ain’t nothing here, but some two-bit singers.” Lafferty reports while exiting another dive.

“I want a burger.” Jenkins cries as he walks behind Lafferty.

I just want to eat something, don’t matter what it is.

“Come on guys, let’s head down the block toward the market. We can pick up some chow there.” I suggest.

As I finish the phrase a couple of Pachucos sporting zoot suits come round the corner.

Lafferty turns, tapping Jenkins on the shoulder to get his attention.

Jenkins darts in front of the Pachucos, his uniform flowing as the air catches it when he lands.

“Hey Muchacho,” Jenkins calls out to the the surprised Pachucos, “Why you helping out the Japs?”

The center Pachuco turns his head left, making eye contact with one of his buddies.

“Come on Jenkins, let’s get some chow.” I call out, moving in behind him.

Jenkins turns to me, while blocking the Pachuco’s path.

“They’re wast’en, while good Amer’cans saving. We can’t let them waste n’more!”

Lafferty pulls up beside me, so all three of us are now blocking the Pachuco’s.

“We ain’t wast’in, we look’in good.” The Pachuco on the right counters Lafferty.

We didn’t come here to fight.

With my right hand I grab Jenkins’ right shoulder, with my left I push his left shoulder, spinning him toward me.

“We’re hungery. Let’s eat.” I say.

Lafferty turns his head toward me.

The Pachuco’s walk on, moving around us as they go.

With his left, Jenkins grabs my hand, twirling me about so my right shoulder brushes the back of the so far silent Pachuco’s jacket.

Damn Jenkins!

The Pachuco taps his buddy while turning toward me, his left arm raised hight.

Jenkins, who’s faster than me, blocks the Pachuco’s arm, while delivering an uppercut into his soft belly.

Collapsing from the blow, the Pachuco screams out.

Now we started something.

The other two Pachucos grab their buddy, lifting him up, while turning to face the three of us.

Bouncing on the balls of his feet, Jenkins is looking for a fight. He calls out “That’ll teach you to waste so much! It’s Un’merican!”

Lafferty gets himself into a fighting stance.

Do I fight?

Once he’s standing on his own again, the two other Pachucos pull their friend with them, attempting to turn to head back the way they came.

Jenkins runs up after them, Lafferty at his side.

I don’t want to fight these guys, I want to eat.

Jenkins pulls the Pachuco on the left back by the collar of his jacket, throwing him to the ground.

Lafferty does the same to the Pachuco on the right.

Both men start kicking the guys. Kicking hard.

“Hey, stop kicking them, we were going for chow!” I yell out as I run up on’em.

As I make it to their sides, Jenkins bends down and starts pulling the zoot suit jacket off of his Pachuco.

Lafferty sees Jenkins doing this, so he starts in on his.

Screaming, flailing with their arms, and kicking with their feet, the Pachucos try to resist, but eight weeks of basic training and drill made Jenkins and Lafferty too strong for these soft city rats.

I look away, not wanting to witness my friends beating anyone.

Why did they have to waste so much fabric on their clothes?

My knees get week. I reach out to hold on to the wall of a building.

Just as I touch the building two patrol men come around the corner.

I turn again toward Jenkins, who is now urinating on the jacket he ripped off the Pachuco.

Lafferty is doing the same thing.

Walk away, just walk away.

The patrol men pull out their batons.

Jenkins calls out “Hey, these Pachucos are Jap agents!”

Without looking at each other, the patrol men start hammering blows with their batons onto the two hapless Pachucos.

The third starts to run.

One of the patrol officers turns and starts chasing after him.

The Pachuco is too fast for the officer, who gives up, returning to rain more blows of his baton down on the helpless man on the ground.

Jenkins and Lafferty zip up.

Turning to me, Jenkins announces “I’m starv’in. Let’s get that chow.”

Lafferty replies “Yeah, I could eat a horse!”

I’m not hungry anymore.

Here is a link to a Cherry Poppin Daddy's song commemorating the Zoot Suit Riots

The Zoot suits riots-June 1943

by dirkdeklein

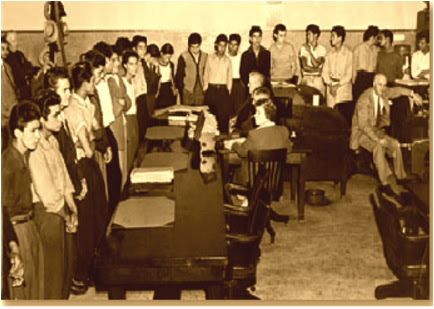

Zoot Suit Riots, a series of conflicts that occurred in June 1943 in Los Angeles between U.S. servicemen and Mexican American youths, the latter of whom wore outfits called zoot suits. The zoot suit consisted of a broad-shouldered drape jacket, balloon-leg trousers, and, sometimes, a flamboyant hat. Mexican and Mexican American youths who wore these outfits were called zoot-suiters. These individuals referred to themselves as pachucos, a name linked to the Mexican American generation’s rebellion against both the Mexican and American cultures.

White servicemen and civilians attacked and stripped youths who wore zoot suits ostensibly because they considered the outfits to be unpatriotic during wartime, as they had a lot of fabric. Rationing of fabric was required for the World War II war effort. While most of the violence was directed toward Mexican American youth, young African American and Filipino Americans who were wearing zoot suits were also attacked

The Zoot Suit Riots were related to fears and hostilities aroused by the coverage of the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial, following the killing of a young Latino man in a barrio near Los Angeles.

The riots began on June 3, 1943, after a group of sailors stated that they had been attacked by a group of Mexican American zoot-suiters. As a result, on June 4 a number of uniformed sailors chartered cabs and proceeded to the Mexican American community, seeking out the zoot-suiters. What occurred that evening and in the following days was a series of conflicts primarily between servicemen and zoot-suiters. Many zoot-suiters were beaten by servicemen and stripped of their zoot suits on the spot. The servicemen sometimes urinated on the zoot suits or burned them in the streets. One local paper printed an article describing how to “de-zoot” a zoot-suiter, including directions that the zoot suits should be burned. The servicemen were also portrayed in local news publications as heroes fighting against what was referred to as a Mexican crime wave. The worst of the rioting occurred on the night of June 7, when thousands of servicemen and citizens prowled the streets of downtown Los Angeles, attacking zoot-suiters as well as members of minority groups who were not wearing zoot suits.

In response to these confrontations, police arrested hundreds of Mexican American youths, many of whom had already been attacked by servicemen. There were also reports of Mexican American youths requesting to be arrested and locked up in order to protect themselves from the servicemen in the streets. In contrast, very few sailors and soldiers were arrested during the riots.

Shortly after midnight on June 8, military officials declared Los Angeles off-limits to all military personnel. Deciding that the local police were completely unable or unwilling to handle the situation, officials ordered military police to patrol parts of the city and arrest disorderly military personnel; this, coupled with the ban, served to greatly deter the servicemen’s riotous actions. The next day the Los Angeles City Council passed a resolution that banned the wearing of zoot suits on Los Angeles streets. The number of attacks dwindled, and the rioting had largely ended by June 10. In the following weeks, however, similar disturbances occurred in other states.

Remarkably, no one was killed during the riots, although many people were injured. The fact that considerably more Mexican Americans than servicemen were arrested—upward of 600 of the former, according to some estimates—fueled criticism of the Los Angeles Police Department’s response to the riots from some quarters.

As the riots died down, California Gov. Earl Warren ordered the creation of a citizens’ committee to investigate and determine the cause of the Zoot Suit Riots. The committee’s report indicated that there were several factors involved but that racism was the central cause of the riots and that it was exacerbated by the response of the Los Angeles Police Department as well as by biased and inflammatory media coverage. Los Angeles MayorFletcher Bowron ,concerned about the riots’ negative impact on the city’s image, issued his own conclusion, stating that racial prejudice was not a factor and that the riots were caused by juvenile delinquents.

A week later, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt commented on the riots in her newspaper column. "The question goes deeper than just suits. It is a racial protest. I have been worried for a long time about the Mexican racial situation. It is a problem with roots going a long way back, and we do not always face these problems as we should." – June 16, 1943.

The Los Angeles Times published an editorial the next day expressing outrage: it accused Mrs. Roosevelt of having communist leanings and stirring "race discord".

On June 21, 1943, the State Un-American Activities Committee, under state senator Jack Tenney, arrived in Los Angeles with orders to "determine whether the present Zoot Suit Riots were sponsored by Nazi agencies attempting to spread disunity between the United States and Latin-American countries." Although Tenney claimed he had evidence the riots were "Axis-sponsored", no evidence was ever presented to support this claim. Japanese propaganda broadcasts accused the United States' government of ignoring the brutality of U.S. Marines toward Mexicans.

dirkdeklein | June 3, 2017 at 8:32 am | Tags: Eleanor Roosevelt, History, Los Angeles, Mexicans, Riots, USA, World War 2 | Categories: Eleanor Roosevelt, History, Los Angeles, Riots, USA, World War 2 | URL: http://wp.me/p73fFh-aUE