Staring up at the well built two-funnel German cruise liner, I can’t help but feel the desire to leave this place.

The heat, the debauchery, the lack of faith. I don’t belong here.

My small launch pulls up alongside the huge ship. Giant white letters on the bow call out for all to see SAINT LOUIS. Similar lettering was visible as we passed the stern just moments ago.

What a beautiful site, these grand ships that travel the seas, taking people on adventures far from their lives; far from who and what they know.

As we near the lowered stairway, I stare up at the crowd of people standing on the mid-deck, where I will be entering the ship.

They look happy to be here.

Gingerly, so as not to aggravate my sciatica, I make my way up the stairs. One foot at a time, step by step, leaning to the left as the pain from pinched nerves stabs down my right leg.

To be free of pain. To be free of this job where I must ascend ship stairs. To be free to leave would be nice. But I can’t because I have to take care of my family and cannot afford to get out of Havana.

Step by step up toward the waiting crew, I pay stern attention to the freshly cleaned steps so as not to slip.

Chains from a job I cannot leave hold me here. Were I to have any skill I could leave this place, leave this job, take my family on a ship like this.

Almost at the top step I look up from below to see who is on deck to greet me. Just as I do my right toe catches the step.

It’s so hard to raise that foot to the same height as the left with the pain!

Luckily, one of the crisp-white uniform clad crew, who is standing right at the top of the stairs, catches me as I stumble.

“Are you ok?” he asks in perfect Spanish.

“Of course, just a little misstep” I reply, hiding my pain behind a facade of clumsy.

A fall at this point, so high on the stairs, could have been very ugly. I must be extra careful. I cannot lose this job.

“Will you please follow me to the Captain?” the clean member of the crew, still holding my arm, offers.

“Certainly” I mumble while looking around at all of the smiling passengers who have gathered to see me board.

Usually passengers are not aware when the immigration official boards the ship. It’s nice to have them notice me.

I can’t help but look at the strong leg muscles of the crew member as they portrude from the starched white shorts. Each muscle flexes and releases in time with the steps of this young German man who is taking me to meet the ship’s captain.

He doesn’t know the pain of sciatica. He’s so young. He has a future.

“May I help you up these stairs?” he asks, standing before another set of stairs leading up to a higher deck.

Pausing for a moment, I assess the staircase.

Seeing my hesitation, the crew member offers “Let me have the Captain meet you here.”

“Yes, that may be best.” I agree.

He runs up the stairs, strong muscles taking leaps over every other step so that he ascends the case within a brief moment. After admiring his agility, I turn to my right to look out over Havana.

I love seeing the city from a ship. It’s as if I’m looking at a completely different world. One bereft of my squalid existence, one with no history for my family, one with a future.

Behind me I can sense an encroaching mass, so I turn away from the city into a collection of faces, each with a story of his own. Men, women, small children all stare at me.

“Sprechen Zie Deutch?” one man asks.

“No” I reply, briskly.

The mass pauses, then begins a slow retreat as I hear the sound of shoes clanking on the metal steps above. Turning back to the steps my eyes rise to meet well-shined black shoes connected to a starched white trouser leg, a slim fitting belt, and a captains jacket before settling on the calm face of a man clearly in charge of all he surveys.

I wish I was in charge of something! To have power. To give orders. To determine the fate and actions of others.

“Greetings, Senor Echazabal, it’s a pleasure to have you aboard the Saint Louis.” The Captain offers.

“The pleasure is mine, Sir.” I reply.

“We have the passports and visas for our passengers right here” he says while turning to one of the crewmen who stands behind him, one leg on the staircase. That crew member hands the Captain a large black book filled with plastic pages. The Captain sets the book down atop a gray ship vent, balancing it so that he can open its jacket to reveal plastic pages, each holding eight passports.

“Do they all have landing permits?” I ask, getting to the point rather quickly.

Everything looks in order, but I have to be thorough. It’s how I’ve kept this job for so long.

“Yes, they are all right here.” He says, offering me a manifest from the back of the book. Each name on the manifest has a document title next to it, outlining what kind of permit the individual has to enter Cuba.

Perusing the list, I notice only a few names have official Cuban Visas.

Most of them have the wrong documents.

“I’m sorry, Captain, but these people have the wrong permits.” I exclaim with authority.

I have something over this man in charge.

“What do you mean, wrong permits?” the Captain replies in disbelief.

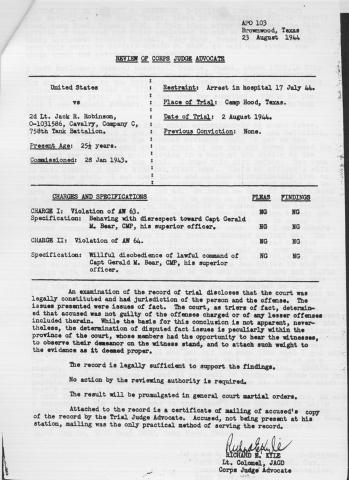

“Earlier this month decree 937 was issued, proclaiming a change in our permit policies, and retroactively invalidating all previously assigned landing permits, except for Americans. It appears that only a few of your passengers have Cuban Visas. They can land, but the rest of your passengers cannot.”

“This is the first I’ve heard of this new rule. What are these people to do?” the Captain pleas.

I surprised him.

“Captain, I cannot let them land here. They will need to leave Cuba.”

I love these moments of authority amended immigration laws offer.

The Captain looks me in the eyes, his hard face softening.

“Sir, I implore you, these people have documents, and NEED a place to land.”

Now I am in charge.

“I am sorry, Captain. These are new rules. I cannot, and will not, offer any exceptions.”

“Sir, please show compassion.” He pulls in close to me, putting his mouth just inches from my ear.

“These people are escaping NAZI Germany, do you know what that means to them?”

Turning so that I can look him in the eyes again, I respond “Yes Captain, but my hands are tied.”

At this, the Captain turns his back on me to face his crew member. In a stern voice he orders “Finish dealing with SENOR Echazabal, I will be on the bridge.”

His face now crimson, the Captain storms up the stairs. His shiny leather shoes smashing against each step with power I can only imagine coming from my weakened legs.

“Sir, please make this quick” the sailor snarks at me. “We have to find these people somewhere to land.

“Of course” I reply, picking up the manifest book to compare with the document list.

On May 5, 1939 the government of Cuba changed its immigration laws to prevent non-Cubans who were not Americans from entering the country. This was a surprise to the crew and passengers of the SS Saint Louis. Of the ship's passengers, 937 were Jews escaping persecution in NAZI Germany. Each, with difficulty, had obtained visas to leave in hopes of starting a new life in the Americas. Unfortunately for these people, Cuba would not allow them to enter. The United States did not allow them in either. Canada also prevented them from entering. The ship returned to Europe, where they were scattered across The Netherlands, France, The United Kingdom, and Belgium. After the war a manifest of the passengers was compared with those still living, revealing that of the 620 Saint Louis passengers who returned to Continental Europe, 254 died in the Holocaust. The banality of evil comes from those simply doing their jobs, as they are the hands of the few who threaten or commit violence against the innocent.