WHAT THE HELL WAS THAT? I scream as I’m thrown face down on the floor toward the rear of the fort.

Just a moment ago I was crouching on the adapted bike seat which shoves itself far higher into a man’s back-end than any object really should go.

I was scanning the densely foggy sky for aircraft from the cramped tail-gunner’s compartment of Skippy, my flying fortress.

Watching the planes to our right and left, I was in a kneeling position, looking out over my guns.

. . .

We’re spiraling and falling.

Flashes of blue, green and brown shoot through the tail window.

The plane is spinning fast!

Whatever happened threw me flat on my face.

Twisting to the right in a tight circle, the fortress spin broke the ammo trunk loose, so it’s now pinning me to the left wall of the compartment.

I need to grab my parachute.

I can’t move.

How will I get to my chute?

Impossible to move, my body is pinned flat against the wall.

I must get to my chute!

Straining every muscle, I try to shove or lift the ammo trunk with all my force.

Nothing, I’m not moving.

I try again, shoving with all my might against the plane’s ribbed interior.

Nothing.

I have to keep trying!

Using every ounce of strength within, my whole body shoves against the wall and the ammo trunk; legs, arms, back, even the back of my head, but I can’t move it.

I can’t move.

I can’t just stay here while this plane crashes.

. . .

I can’t move and I can’t stay.

. . .

I have to move.

With what’s left of my energy, I compel myself off the wall, pushing every last sinew until the heat of the pain forces me to stop.

I can’t.

I can’t move.

I can’t get out.

I can’t stop this.

. . .

Is this it?

Falling to the ground in a plummeting plane is how I die.

This is how I die.

THIS IS HOW I DIE! I yell, girding myself with the vocalization of this realization.

In another few minutes I’ll be dead.

. . .

Time is slowing down.

Looking up through the tail window I can see only fog above.

There is no sense of place.

No here, nor there.

Do not be anxious about anything.

In every situation, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to G-d.

The ribs of the plane dig into my body as I’m forced ever more against its hard metal walls.

“Have I not commanded you? Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged, for the Lord your G-d will be with you wherever you go.”

Images begin streaking across my mind.

My mom’s face.

My dad reaching out his hand to me as I prepared to board the train when I left for basic training.

The softness of Emily’s lips when we last held each other.

“Even though I walk through the darkest valley, I will fear no evil, for you are with me; your rod and your staff, they comfort me.”

What have I done with this life?

I could have given the toy car back to Jack.

. . .

Why did I not ask Emily to marry me?

. . .

What difference have I made?

. . .

“Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid or terrified because of them, for the Lord your G-d goes with you; he will never leave you nor forsake you.”

. . .

What is this all for?

. . .

I’m not getting back to Kentucky after all, am I?

. . .

Why is this taking so long?

If I’m going to die, why does it have to take so long?

Get it over with!

GET IT OVER WITH ALREADY!

This is not ok.

Come on!

HURRY UP, DAMN IT!

. . .

“So do not fear, for I am with you; do not be dismayed, for I am your G-d. I will strengthen you and help you; I will uphold you with my righteous right hand.”

. . .

Time is fascinating.

Most of it we don’t even notice.

It goes by.

Yet, at the end, it takes FOREVER!

If it had taken this long through everyday life, I’d be dead by now.

. . .

WHAT IS TAKING SO LONG?

. . .

Going to college is no longer on the table.

I would have liked college; the learning, the slower pace, the peace.

This falling is peaceful.

. . .

Am I already dead?

Is this what death feels like, this peace?

The plane has been plummeting for so long, maybe I’m already dead.

If this is death . . . I’m ok with it.

. . .

A raspy swishing sound breaks my thoughts.

Looking out, no longer up, through the window I see the tops of trees float away as the fort scrapes along them.

GROUND!

. . .

We’re gliding down!

. . .

WE’RE NOT FALLING, WE’RE GLIDING DOWN! I yell out.

Just then, the plane comes to an abrupt and jerked halt.

Thrown forward, I bump my chin against a side-rib of the plane too hard, but the ammo trunk is moved a bit in the crash.

That’ll bruise.

. . .

We’re on the ground!

WE’RE ON THE GROUND! I yell.

I’M ALIVE!

I’M ALIVE!

I’M ALIVE!

I’M ALIVE!

. . .

I’ve got to get out.

The ship might be on fire.

Shoving with what energy I have left, I’m able to nudge the ammo trunk a bit.

It’s working now!

Gathering all the strength in my arms and legs, I shove again.

Again, a bit of a nudge.

Keep at it.

Use it all up, get out!

UUURRRGGGG!!!!! I grunt as I shove again.

More movement, it’s sliding now.

AAAUUURRRHHHGGGHH!

I GOT IT!

I can rise!

The ammo trunk is finally off of me.

Raising my sore, and exhausted body off the wall of the downed fort, I dig my way out of the strewn shell casings, broken ventilation station, and other debris which had been tossed about as the plane spiraled down.

My eyes scan the space looking toward the bulkhead door.

Wow, the side of the ship is bashed in.

Glad I wasn’t pinned against that wall.

Turning the handle on the bulkhead door, I’m shocked by what I see.

Or, don’t see:

THERE’S NO PLANE!

. . .

The tail must have come apart from the rest of the plane, coming down by itself.

What happened to the rest of the crew?

As I remove my oxygen mask and headset, I scan the wreckage for another pair of shoes.

Picking them up, I then exit the tail compartment of what’s left of Skippy.

I gotta get away from here.

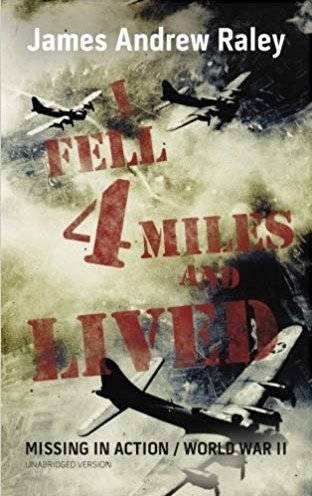

Sgt. James Radey was the tail gunner of “Skippy” a B-17 from the 301st Bomb Group, 253rd Bomb Squadron. He became the only survivor of his crew on January 11, 1944 when his squadron was in route over Greece. Visibility due to weather was barely past the wingtips of the aircraft, causing two bomb groups to collide head-on. Eight B-17s were destroyed, claiming 64 airmen’s lives. 17 men survived the crashes, Raley the only one to do so without using his parachute. Walking away from a four-mile fall in the broken tail section of a destroyed bomber, Raley suffered a cut to his chin and some bruises on his shoulder. Miraculously, the bomber’s ripped away tail section, with Raley inside, had just the right lift and weight distribution for it to “float like a leaf” and land relatively softly in a clump of pine trees. This was Raley’s 13th mission.

After the war, Raley visited the families of all of his lost crew, married, wrote an autobiography of his experience and retired as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Air Force after serving in Korea and Vietnam. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. From the day of the crash onward, he always considered 13 his lucky number.